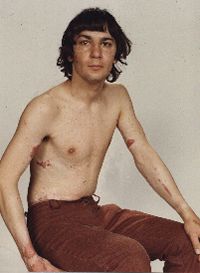

Burn Survivor David von Janowski's Story

The Accident

Although it was September, the summer had been long and I awoke to yet another sunny morning. Being 20 years old, rising in the morning meant getting up any time before ten o'clock, it was five to ten. Having completed two years of study for a Technology diploma I decided to cycle across America for charity and this trip here to Germany was a practice run. I was staying with my uncle in his flat in Germany. I had a flair for repairing most things, and for this reason I was always welcomed to stay with anyone I knew.

The flat was empty. I looked out from the second floor balcony to see if the world was still there. In the distance my aunt was making her way to the local shops, with her daughter by her side. Below, on the forecourt, my uncle was repairing his motorcycle.

I dressed and had breakfast. I had to carry everything I needed for a three month journey on two wheels and my wardrobe was limited. All my clothes were lightweight items. I also had to carry a lot of thoughts, and this trip was going to help me decide what to do with my life, but not in the way I had expected.

I had other interests, apart from repairing things. I hated and feared sport at school and always developed cold symptoms the day before. Regular timed illness did not prevent forced participation. My parents did not understand. I could not see the point of running up and down a windswept field chasing a bit of leather filled with air, only to be pushed over by enthusiastic participants, into a muddy puddle.

When I reached the Sixth form I could choose my 'sporting' activities. I chose horse riding. No more colds, I was a natural and quickly became hooked on the idea of leaving home as a working pupil. My parents, however, had visions of my becoming some sort of technical expert.

I averaged 100 miles each day on my practice cycle run across Germany. This was my fifth day at my uncle's flat and I was planning to leave the next day, Sunday. I went downstairs to see how my uncle was getting on with his repairs. He was nowhere to be seen. His motorcycle was there, lying on its side on the grass. I looked around, and guessed that he had gone down to the cellar to fetch some tools, so I waited.

It was half past eleven. I had not noticed that the motorcycle was alight. The flames were not visible in the sunlight as they licked around the petrol tank. They were not large flames, possibly being fed from a small oil spillage around the base of the tank. The flames generated heat within the petrol tank, the air expanded and within seconds the cap on the tank blew off. Petrol shot out horizontally and caught the flames. The pressure was sufficient to engulf me in a ball of fire.

There was not a bang as the petrol caught light, it was more like the sound of a parachute opening; a kind of woosh My immediate reaction was to close my eyes and cover my face with my arms. I felt a pain on my left arm, as if someone had spread very hot fat all over it. I shook my arm to try and remove whatever was causing the pain, but this caused the flames to flare even more. I opened my eyes and realised that I was alight all over. I shouted in pain; my brain was swamped with pain messages, but the pain was coming from everywhere. As the burning continued nerve endings became damaged and sent no more pain messages. I did not realise that my legs had taken much of the fireball. I was wearing shorts and a thin shirt. Now, in shock and unable to do anything about the pain, I decided the best thing to do was to remove my petrol soaked burning clothes. I took off my shoes and socks, shorts, pants and shirt which were all burning. I was now no longer alight. I then became rather self-conscious as I was standing outside with no clothes on. I ran indoors, up two flights of stairs and entered the flat.

I thought, how nice it would be to do something ordinary, like maybe sit down and watch some television, but something told me I should have a cold shower. I went into the bathroom, stepped into the bath and gave myself a cold shower. I remember seeing a large blister, about the size of a rugby ball, on my right leg below the knee, I detected the smell of burnt flesh; all this told me that I was in need of hospital attention.

I wrapped a towel around myself and went back downstairs into the sunshine. I saw my footprints in the grass, dark burnt patches, coming from a large black circular area about six feet in diameter; bits of clothing were spread about and still burning. From somewhere a man wrapped me in a blanket and led me to his VW 'beetle'. I do not remember what he said or what he looked like, but I guessed he was taking me to the hospital. As he drove along the road, we met an ambulance coming towards us with bells clanging. He stopped and somehow I was transferred from his car to the ambulance.

In the ambulance I was given two pain-killing injections, one in each thigh. This I thought was a waste of time as I could not remember being in pain. I was lying on my back on a stretcher. When the ambulance stopped I was wheeled into the hospital and greeted by about ten faces looking down at me. It was only then that I started to worry, the expressions of hopelessness on their faces told me everything. I had received burns to the whole of my body, apart from small areas of skin covered by my ankle boots, shorts, and the skin under my watch. The hospital was for general accidents and had no facilities for treatment of extensive burns. I took off my watch and handed it to one of the nurses; I knew that I was going to die and had quickly resigned myself to the fact. I knew that burns could be treated by grafting, but my burns were such that there was nowhere to take grafts from.

Moving Hospitals

My next recollection was of lying in a bed in a poorly lit room. I was lying on metallised foil and a nurse was sitting in the room. I tried to look up but the effort was too great, I wanted to look at the light above the door. The room was not poorly lit, my eyesight had been damaged, I was looking through a fog and the swelling made it difficult to open my eyes. I asked the nurse if he could play chess. It must have been Sunday. I do not know if it was the drugs or shock, but I had no fear of dying, I was not in pain. I didn't have to worry about making any decisions about my future.

Several times I talked to the nurse. "Why are you sitting there?" I said, "Can you play chess?". For some reason I had a fixation about playing chess. It seemed such a waste of time, us both just doing nothing in this dark room. I do not remember his answers.

Whilst I was lying in the room things were happening. Arrangements were being made to move me to the Berufsgenossenschaftliche Umfall Clinik in Duisburg. This was a special hospital funded by industry to treat serious industrial accidents.

Sometime on the Monday, I was placed on a stretcher and taken along the hospital corridor. I was not appreciative of the tour, being shown all those ceilings. However, when I saw the outside of the hospital building and then blue sky I did wonder what was going on. Apparently, road traffic had been halted and cows had been herded up to the far end of a field opposite the hospital. A helicopter was waiting for me, and I was wheeled across a road through a gate into the field. The helicopter was a special sterile transport ambulance booked to move me to Duisburg. I was lifted into the air ambulance and as ear mufflers were placed on my head to deaden the noise I looked up and said thank-you to the pilot.

I woke up in a bed in the special burns unit, a sterile room which had five other patients. I still could not see very well, but could make out eight bottles, four each side, hanging upside down and supplying liquid and food via drips, to my body. Apparently, people who are badly burned die of dehydration. I was also wired to a digital thermometer. I could hear a radio or television, the noise forced me to try and understand what was being said, and this required effort, something I was lacking. I asked if the noise could be turned down but it wasn't. I also asked what was in all those bottles, champagne maybe?

The first person to speak to me in the new hospital was a doctor Brandt. Brandt is German for burnt, a coincidence. I could not see his face. With my blurred vision I could make out a blue surgical hat, a white face mask and blue surgical coat and trousers. I later discovered that his shoes were also covered in surgical sterile material. I could see his eyes but not his face. He spoke in German but I could work out what he was saying. "You have been badly burned. We will have to wait until some of your skin has healed and then use this to cover your more serious burns. We will operate in a few days".

I asked, "How many operations will I have?" He said, "You will probably need to have about thirty operations." I do not think he knew my name, either that or he called my by a German equivalent, but his matter of fact impersonal attitude was probably trying to cover his own feelings of doubt about the likely success of the operations. I started to shed some tears. They were not tears of joy or sorrow, just tears.

Apparently, over the weekend I had died for four minutes. I was resuscitated and then kept alive until I could be moved to the special hospital. I had required over thirty-six pints of blood. With all the pain-killing drugs I knew little of the weekend's events.

The drugs removed much of my consciousness, this was the best means of alleviating the pain, but they did not remove my feelings of thirst. I was having small drinks from a glass through a bendy straw. Anyone ill in bed can do no better than drink this way. I fantasised about having drink parties, with all sorts of exotic fruit drinks.

I had to have a saline bath before my first operation. I said I would try to walk the five yards to the bathroom. The nurse watched carefully as, after she removed the top layer of foil, I got up out of bed and took a few careful steps. This was all I could manage. I collapsed into waiting arms. I was very hot and kept saying, "It's hot in here, I'm so hot." I sat in the bath and she carefully sprinkled water over me. I asked if I could drink the shower water. It was special spring water not from the mains supply, and tasted very different from the ghastly stuff I had been drinking so far. My sense of taste seemed to have been exaggerated either by the drugs or by the lack of solid food. My only demand from the nurses that from then on was they fill my glass with water from the shower head in the bathroom.

The First Operation

I had been in the second hospital around a week, and it was time for my first operation. I was still on pain-killing drugs and knew very little of what was going on around me. The television was turned on all the time and when no programs were on, a jingle would play about once every five minutes, a strange tune that made me feel as if I had died and been reborn, and was now on some strange planet where nothing of my life as it was would ever be the same again. From my bed I looked out of the window; all I could see were sky and clouds.

The thirst was a problem. I was not allowed to drink before the operation. I could have a damp spray directed into the back of my mouth but that was not enough. I was given drugs to prepare me for the operation and later had my first trip outside the room, where I was wheeled to the theatre via a lift, on a trolley. I saw more corridor ceilings. In the operating theatre I was told to count to ten. I could do this in German, but I think I only counted up to four. Waking from the operation, I was bandaged all over from chest to foot and my arms. I could not use my hands; my fingers and thumbs had been individually bandaged. Both my legs had been drilled through bone and threaded with four metal spikes. These metal spikes were clamped to a frame support holding my legs about one foot apart at the knee. It was as if I had been crucified and hung by my legs. My knees were bent at forty-five degrees, I was not very comfortable. All this was to prevent the skin grafts from moving whilst the process of healing continued.

The areas of my skin that had healed sufficiently, had been used to provide skin for the badly burned areas. The healthy skin had been removed in thin layers, pricked with small holes and stretched to cover a larger area and then grafted onto my legs. Surface burnt skin will only heal along three millimetres of its edge, so the stretched holes could be no bigger than six millimetres. I now had donor areas which were as painful as the burnt areas.

My legs would look like a patchwork. I asked for a mirror to see my face. It appeared that I was to survive this ordeal and I wanted to see what I looked like. I was not given a mirror. Why couldn't I have a mirror? It was not through fear that I wanted to see myself, it was curiosity. But not being allowed a mirror made matters worse. My hair had been burnt, my face was still swollen and my eyesight was foggy. Over a week had elapsed, so what did I look like?

Emotions, Pain and Other Patients

I was very emotional, the nurses were pretty and I wanted to marry all of them. One nurse, Monica, would telephone me from her flat in the evenings. I did not have any visitors; they were not allowed, so her phone calls were my only link with the outside world. She would play records that I knew and this established a link between this hospital world and my life before, when I could ride a horse or cycle into the country. The records slowly brought home to me the reality of what had happened. I had another twenty-nine operations to go; I must be in a mess.

The only thing I had to worry about was pain. Everything hurt when I moved, when I breathed my chest moved and the bandages rubbed. I had to lie on my back which was burnt, my front was burnt. I could not lie without feeling pain. But I was not miserable. For some reason I had not died, I wonder why. I started to notice other patients in the room. There were six of us. To my left was Heintz who had been thrown out of a flat by an explosion of industrial carpet floor-cleaning chemicals. He had hung onto the balcony rail to stop himself falling. His visitors were clad in surgical gowns, shoes and hats just like the doctors and nurses. One visitor showed me a picture of Heintz before his accident, the only way I could recognise him was by his eyes and this did upset me. His face was not the same. I then dawned on me that Heintz had been very badly burned about his face. I had seen him only as he was after his accident, so not making a comparison I could not say that he was badly disfigured, but he was.

Ouver, a boy about twelve, was on the other side of me. I had suffered his cries of pain almost as much as he had. He had been watching the trains on a bridge. The next thing he knew he was in hospital. He had fallen from the bridge onto high voltage electricity cables, and from there onto the track. He had lost a leg and suffered burns to the middle part of his body. His father had to donate skin for grafting.

Mustafa, opposite, had about twenty operations on his foot. He had been working in a smelting factory when molten metal was poured through his foot. The repair work on his foot involved not only skin grafts but bone grafts as well.

An Irish woman had heard that an English speaking patient was in the hospital and she sought me out. I told her about my accident. She had been involved in a bad car accident and almost every bone in her body had been broken. She had lots of bone graft operations and was going home soon after spending a year in the hospital.

The other patients in the room were not well enough to talk. In the room next to me was an elderly patient who had been badly burnt. I did not know the details but a nurse told me he had been in intensive care here for two years and died several days ago.

Even though I was covered in bandages I was still expected to do physiotherapy. The nurse was friendly enough, until she expected me to move my arms about. I realise now that this was important, otherwise my joints would go solid and I would not be able to bend my arms at all. It did hurt. The bandages scraped raw skin as I moved my arms up and down, bent my elbows and moved my fingers. I always shouted "Oh no, no, not you, not again", whenever I saw her, but she knew that I knew I must "bewegen", which is move in German.

The Second Operation

My eyesight was less cloudy and I felt that maybe I was getting better. Then I was told I would soon be ready for the second operation; more grafts to my legs. The skin on my legs had been burnt to within one millimetre of the bone and a lot of work needed to be done if I was not to lose them. Well I've made it this far I thought, what's another twenty-nine operations?

The second operation put me in more pain. I was being given a form of cocaine injection to allow me to sleep each night. This would knock me out until the early hours of the morning, but they wouldn't give me any more as the drug was addictive. My legs were still on the pin and wire frame but I was allowed visitors. My friends from Holland came to see me. I became acquainted with them through a Dutch shortwave radio station and knew them well. They heard about my accident on the news and in the papers and had told the radio station about my accident. I could not have a radio in the room because it would have had to have been specially sterilised.

Each day I was having another finger unwrapped. I felt like an overgrown advent calendar. Physiotherapy became more aggressive as bandages were removed. Finally, I was allowed to have a mirror. I had enough free fingers to hold one. I didn't look straight away, a moment to fear, even though desired. I saw a twenty year old male, someone I hadn't seen for nearly a month, with peculiar shaped hair, but no obvious disfigurement to the face. I had a small mark but I could grow a moustache over that. My right eye had a small line where my eyelids met.

I still didn't know if my legs would be saved. Doctor Brandt paid me a visit. "You have healed well", he said. "I am surprised at how you have made progress. You must have been very fit and healthy before your accident. If you had been a few years older you would not be here now. I think only one more operation will be necessary". "You will be having a visitor from the first hospital where you stayed." So much for vegetarians not being healthy, I thought.

Only one more operation, but I thought I was going to have hundreds of them; and who was the visitor. Up to now, my most frequent visitor had been the hospital pastor. I told him I was not religious but it didn't matter to him. I said I was so pleased that he visited me; he could speak English and that meant so much to me. I always had a tear in my eye when he came to see me. One day he came with a big book. Ugh, I thought, a bible, well it's the thought; but . . it wasn't a bible! He had bought a huge German English dictionary with over two thousand pages. It was too heavy for me to lift. He had written inside, "My dear patient David, in the Umfallklinik, from the catholic hospital priest Karl, 27/9/1977". He had put a lot of thought into this gift. I was really overwhelmed.

Every three days I had to have the bandages replaced. This was by far the worst ordeal to go through, but it could not be avoided. I had to sit in the saline bath. Bandages were unwrapped, that was not too bad, but underneath the bandages were special gauze strips which had to be removed. This involved gentle work with the shower head, and an inch by inch peeling of the material which had stuck to open wounds. I was one big open wound. I was drugged before each bath. The only perk was a drink from the shower head.

My special visitor came, a nun. It seemed strange that I should be visited by a nun. The nun was also a nurse, a nurse from the first hospital I stayed at. I was pleased to see her because she managed to piece together the events after my accident. The first hospital "Rheinburg Krankenhouse" was small, run by nuns and used to dealing more with births of babies. They had done their best for me and it was only by luck that a bed had become available in Duisburg; without specialist treatment I would have died. She gave me a small book of "thoughts". I would have to wait until I could lift my dictionary before reading the poems.

The Third Operation

This was the day of my third operation. I was now familiar with the routine, they wake you up, take away your drinking straw, try to make you sleep with drugs, then wake you up again by moving you about on a trolley, and on top of that you have a maths test counting in German. The last operation was to remove the pins and free my legs from the frame. I awoke in a different room. I was no longer in intensive care, my legs were not supported but my knees were fixed at forty-five degrees, no doubt as a result of the month's lack of movement. I was no longer surrounded by bottles and monitoring machinery.

Things started to improve. I developed an appetite. I started on soups, but I was a vegetarian and soon became picky. On Sunday evenings the kitchen closed and we would be given rather unappetising sandwiches, some with meat. Apparently, the hospital had a flourishing rabbit population in its grounds. I found out why on Sunday. As soon as the nurse had gone, all our sandwiches were thrown to the eagerly waiting rabbits. What they didn't eat was eaten by birds. "Who wants chips?" shouted one of the patients. I was amazed, chips in hospital! The kitchen did not have chips on the menu. Everyone wanted chips, including me. One of the more mobile patients put on a dressing gown and slippers, collected some change and sneaked out of the room. "Where's he going?" I said. I learned that just outside the hospital in the high street was a chip shop. It was a daring venture, nurses can be vengeful in sneaky ways. We all enjoyed chips that night. When the nurse came to collect the empty sandwich plates the room still smelt like a fish and chip shop and we were given funny looks and a waving finger. Both rabbits and patients slept a little more contently that night.

When Dr Brandt came to see me I did not recognise him; he was not wearing sterilised clothing. I explained that he should cover his mouth and forehead with his hands, then I could recognise him. He did this, rather amused, and I said, "Yes, it's you, doctor," I was told that I should make an effort to get out of bed and start using my legs. No more operations would be necessary but I must start to walk again.

I was allowed to have a radio and this gave me contact with the English language. I was also given a sack full of mail sent from all over the world. The Dutch shortwave station had broadcast massages to me which I had not heard, and listeners had taken it upon themselves to write. Now, out of intensive care, I was given this mail. Over five hundred cards and letters arrived, people even sent money.

As my burns healed, I was getting back more movement in my arms and hands. The dead skin started to peel, rather like after sunburn. I was peeling and itching all over. My first attempts at walking were not a success. I could not straighten my legs and I fell onto supporting nurses arms. I was still suffering physiotherapy torture, now lifting and lowering my legs in bed and trying to straighten and bend my knees.

When hospital food was served we were never given the full complement of cutlery. One had to eat everything using only a fork or spoon. I always had to ask for a knife; this particular day the nurse told me to get the knife myself. "Right," I said, "That's it. I've had enough of this. Where are they then?" "Erste rechts," she said, which meant first on the right. Well, the physiotherapy must have done something at last. I got out of bed unaided and waddled like a duck, out of the room and down the corridor to get my knife. As I came out of the door Dr Brandt was walking along the corridor. I walked towards him as he had not moved out of the way. When I was close to him I said something about Germans not using knives and he hugged me. "You are walking," he said, "You will be going home soon I think." He was smiling. I had not given it a second thought but I had walked unaided for the first time in two months, on legs that I had nearly lost, with a life that I nearly lost.

I went back to England a month later, three days before my twenty-first birthday. Before my return to England I visited the staff at the first hospital and returned to the spot where I had the accident. They were still there . . . my footprints in the grass.

David von Janowski - Burn Survivor

Copyright © David von Janowski (June 2001) All Rights Reserved.

Click/tap

here to go back to the main "Your Own Stories" page

Click/tap

here to go back to the main "Your Own Stories" page